José Morán

Market Intelligence and Innovation Advisor - Invest Guatemala

Understanding the role of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in an economy is essential for designing development strategies that position it as a key driver of growth. This report defines FDI, specifies the criteria an investment must meet to qualify, and describes its main components. It then provides a quantitative, descriptive analysis of FDI’s behavior over time, the evolution of each component, its relative importance within Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and a comparison with countries that compete with Guatemala in attracting foreign capital. Together, these elements lay the groundwork for deeper analyses that can inform concrete policy and business action.

According to Mexico’s Ministry of Economy (2016), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is defined as “investment with the purpose of establishing a lasting relationship for long-term economic and business objectives, made by a foreign investor in the host country.”

The concepts and classifications used to measure FDI are based on the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition (BPM6) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and on the OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment. This framework ensures international comparability of statistics, which applies to Guatemala as well as to other OECD member states.

According to the Bank of Guatemala (2021), for an investment to qualify as FDI, it must meet the following conditions:

• Operational control: Ownership stake greater than 50%.

• Significant degree of influence: Ownership stake between 10% and 50%. (This represents an important opportunity for Guatemalan entrepreneurs, who may establish joint ventures with these firms, leveraging both their experience and capital in diverse markets.)

• Long-term relationship: Duration of more than one year.

Foreign Direct Investment in the Region

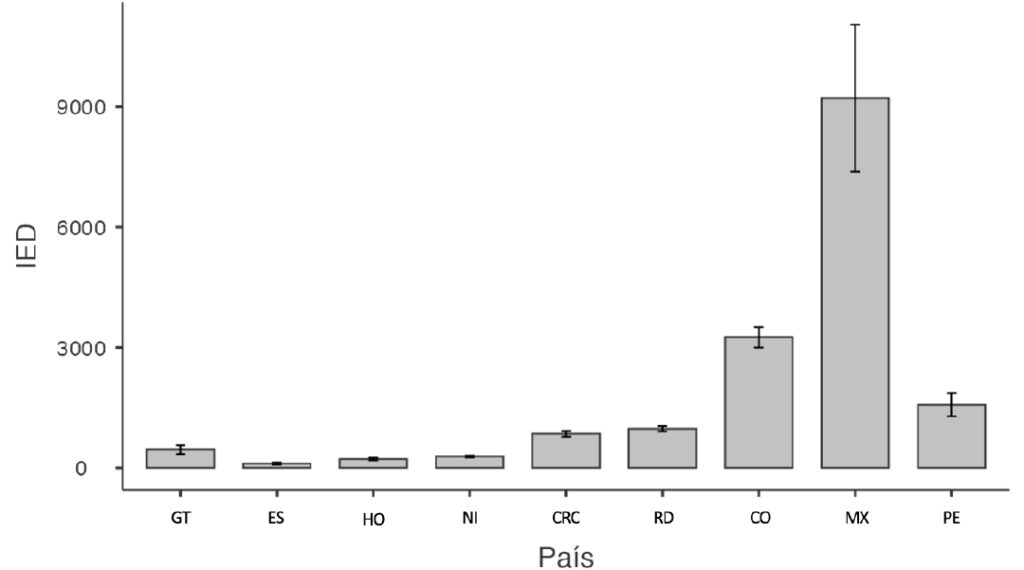

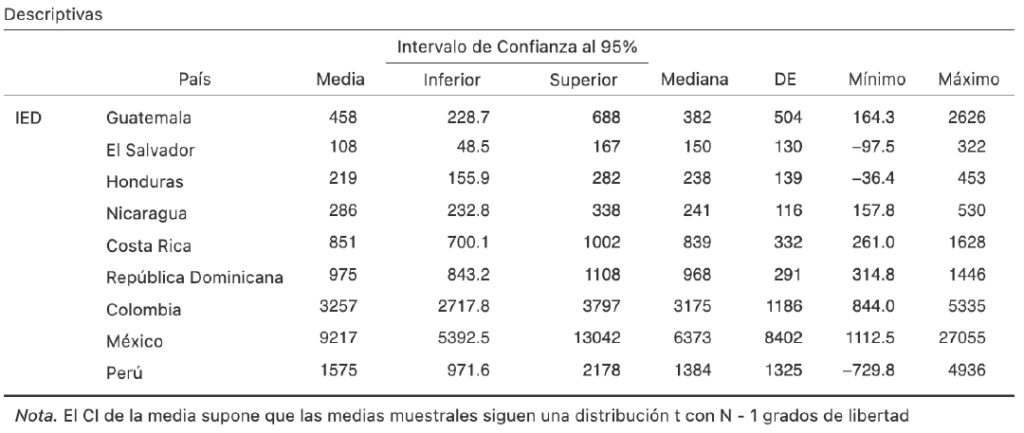

This analysis focuses on Central America, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru—countries that share characteristics with Guatemala and compete for foreign investment inflows. Each of these countries has recorded different levels of FDI over the years. To illustrate the scale of these flows, Table 1 in the Annex presents quarterly descriptive statistics for the period 2020–2025 (up to the first quarter). Mexico leads with the largest FDI inflows, ranging between US$ 5,392.5 million and US$ 13,042 million per quarter, with a median of US$ 6,373 million, consolidating its position as a regional leader alongside Brazil. In contrast, Guatemala’s quarterly inflows range from US$ 228.7 million to US$ 688 million, making it a leader within Central America, though still below Costa Rica and Panama, whose quarterly inflows are roughly double those of Guatemala.

Figure 1. Quarterly FDI Distribution, 2020–2025

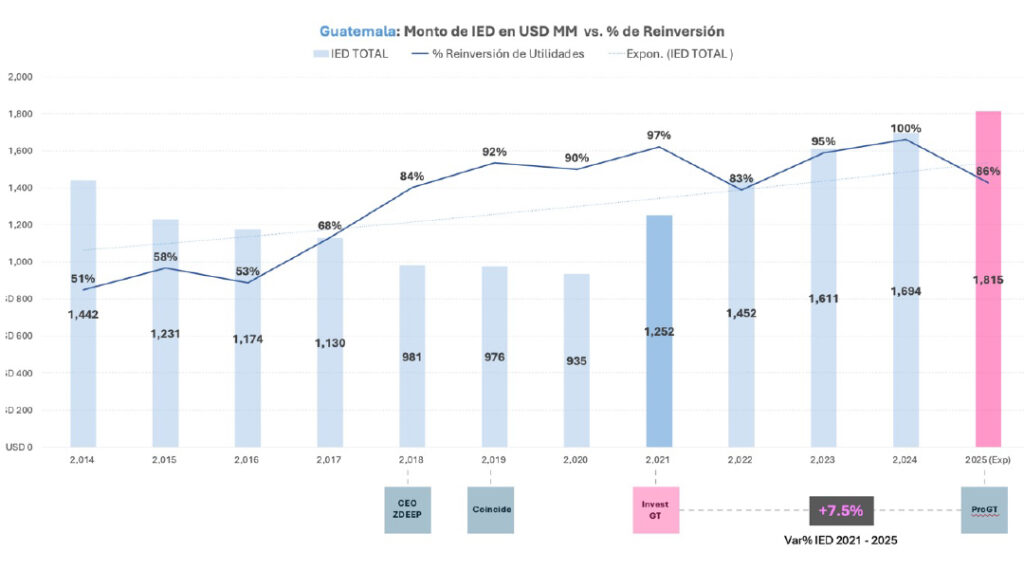

In Guatemala, FDI has shown a clear upward trend since 2021, with average annual growth of 7.5% through 2024. For that year, inflows are expected to nearly double those recorded in 2020. This performance reflects the impact of initiatives such as Invest, which not only generate short-term results but also strengthen long-term growth prospects when strategic objectives remain consistent.

Figure 2. Annual FDI Flows to Guatemala, 2012–2025

Importance of FDI in the Economy

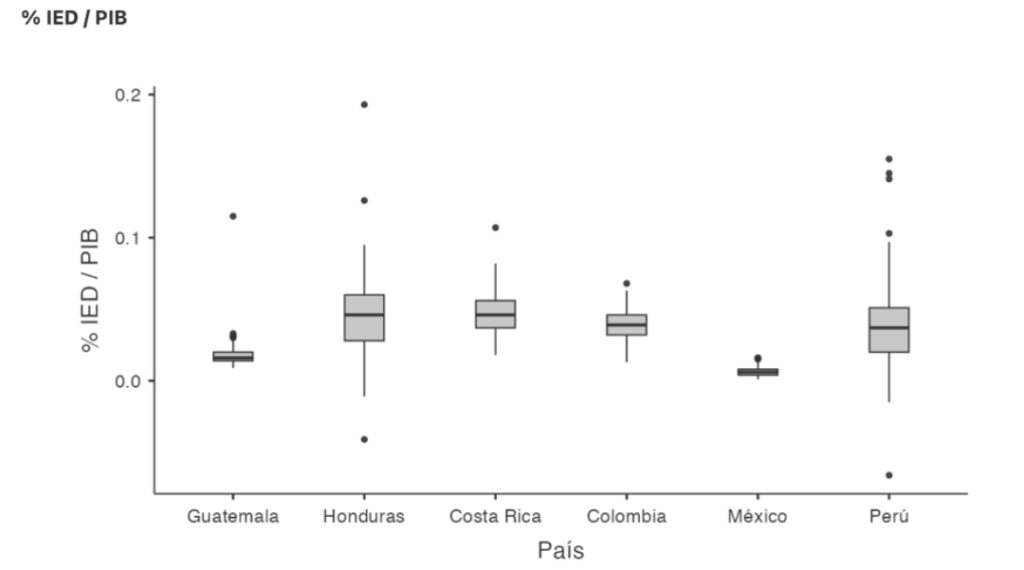

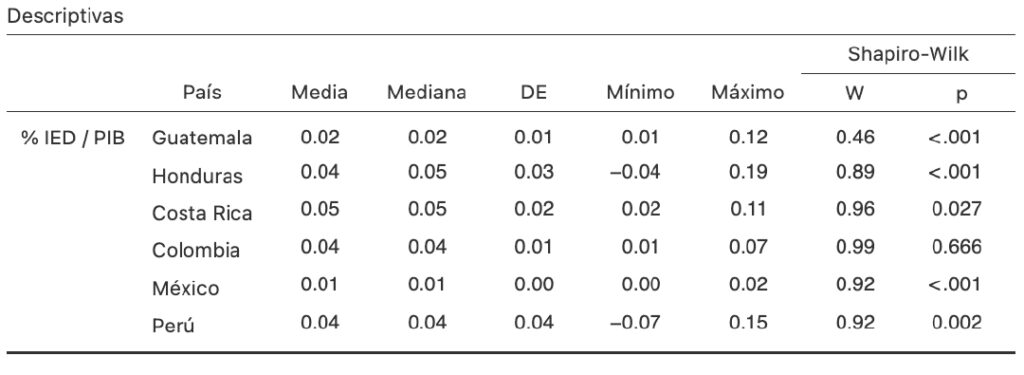

The importance of economic variables is often assessed by their relative weight within a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross National Product (GNP), depending on the case. In this regard, FDI in Guatemala has represented, on average, about 2% of GDP, a figure not far from the 3% regional average (see Table 2 in the Annex). From a visual standpoint, the boxplot reveals that the relevance of FDI within regional economies shows significant outliers, particularly in Peru and Guatemala.

Figure 3. Boxplot of the FDI/GDP Ratio

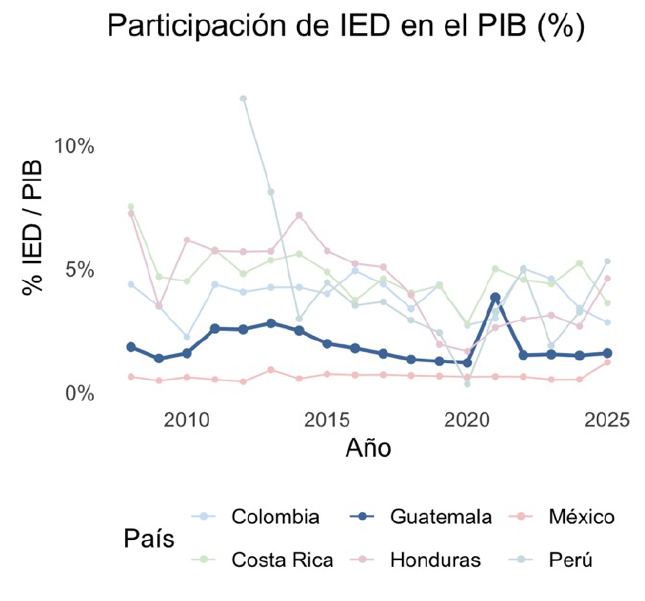

It is also important to analyze how this variable has evolved over time across different countries. In Mexico, its relative importance can be considered “low,” given that the economy exceeds US$ 1.5 trillion. In Guatemala, represented by the blue line, the series fluctuates between 1% and 3%, with few exceptions—making it the second lowest among the countries analyzed. By contrast, countries such as Costa Rica, Honduras, and Colombia reach FDI levels close to 5% of GDP, demonstrating a greater integration of foreign capital as part of their economic structure.

Figure 4. Evolution of FDI Participation in GDP

Components of FDI

The components of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) refer to the types of financial flows that form part of the market operations through which companies establish control or ownership participation, as previously described.

According to the Bank of Guatemala, the main components of FDI are as follows:

• Equity and other participations: Contributions to the capital of new companies (i.e., new equity investment) and net increases in the equity accounts of existing companies (share capital and other equity). Closures are recorded in this category with a negative sign.

• Reinvestment of earnings: Accounting losses reported by companies are recorded as a reduction in reinvestment. Conversely, when profits are generated, they may either be distributed or reinvested. The amount of reinvested earnings during a period determines the value of this component.

• Debt instruments: These represent net financial flows of assets and liabilities between parent companies and their affiliates, including trade credits, accounts receivable or payable, purchase or sales advances, and all loans granted or received.

The importance of new investments lies in their potential to generate new employment opportunities, while reinvestments reflect the continuity of business operations within the country—often implying the expansion of activities, which also creates jobs.

Meanwhile, debt instruments may be directed toward capital expenditures (CAPEX) or operational expenditures (OPEX) depending on each company’s specific needs.

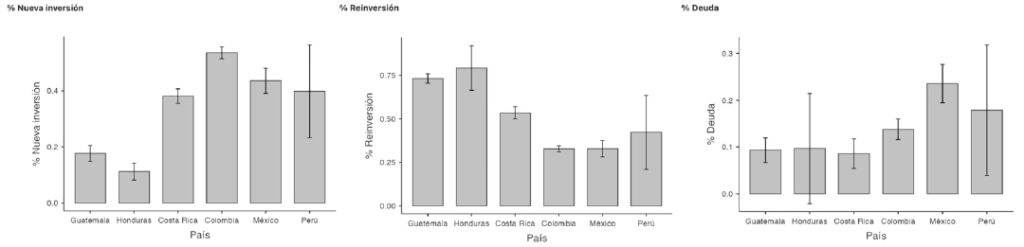

As shown in Table 3 (see Annex), reinvestment dominates at the regional level, while debt instruments account for a smaller share. New investment represents between 29% and 39% of total FDI, whereas reinvestment ranges from 45% to 60% when analyzed jointly. Table 3 further details the composition of FDI by country.

Figure 5 illustrates the differences in the contribution of each FDI component among the countries analyzed. Likewise, the historical evolution of these components offers valuable insight into the trends that each one follows. In the case of Guatemala, there is a clear upward trend in the development of industrial spaces, which has driven new investment growth.

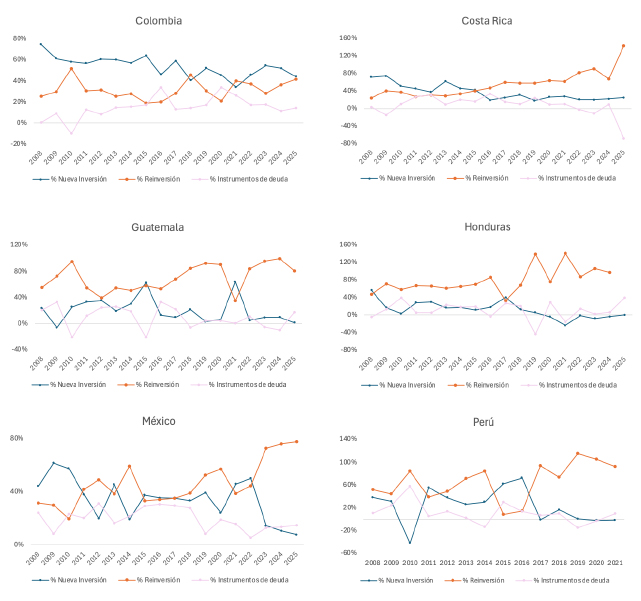

Figure 5. Quarterly FDI Components in the Region by Country, 2008–2025

Figure 6 presents the evolution of each component for the countries under analysis. It is noteworthy that the blue line, representing new investment, shows a downward trend in most countries, except in Guatemala, where the share of new investment displays random fluctuations and notable peaks, particularly in 2015 and 2021. This downward trend is most evident in Mexico, Peru, and Costa Rica, especially as the orange line, representing reinvestment, shows an upward trajectory over the same period.

Figure 6. Annual FDI Components by Country

Comparative Analysis

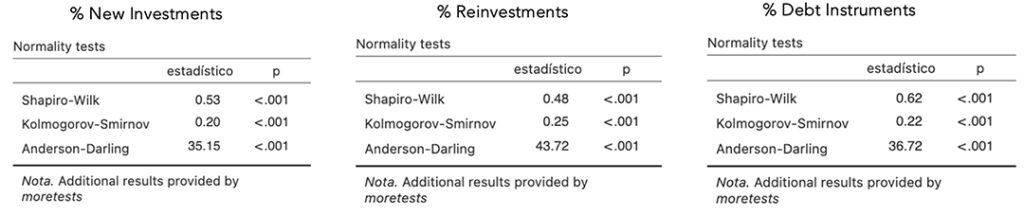

For the comparative analysis of each FDI component across the selected countries, normality tests were first applied to determine whether the appropriate statistical tests should follow a parametric or nonparametric approach. Detailed results of these tests can be found in the Annex section.

FDI and Employment in Guatemala

One of the primary impacts expected from any type of investment—and particularly from Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)—is job creation. International companies that establish operations in the country generally do so within the formal sector, complying with all applicable labor regulations.

In this context, the data reported by the Guatemalan Social Security Institute (IGSS) on the number of registered contributors each year become especially relevant.

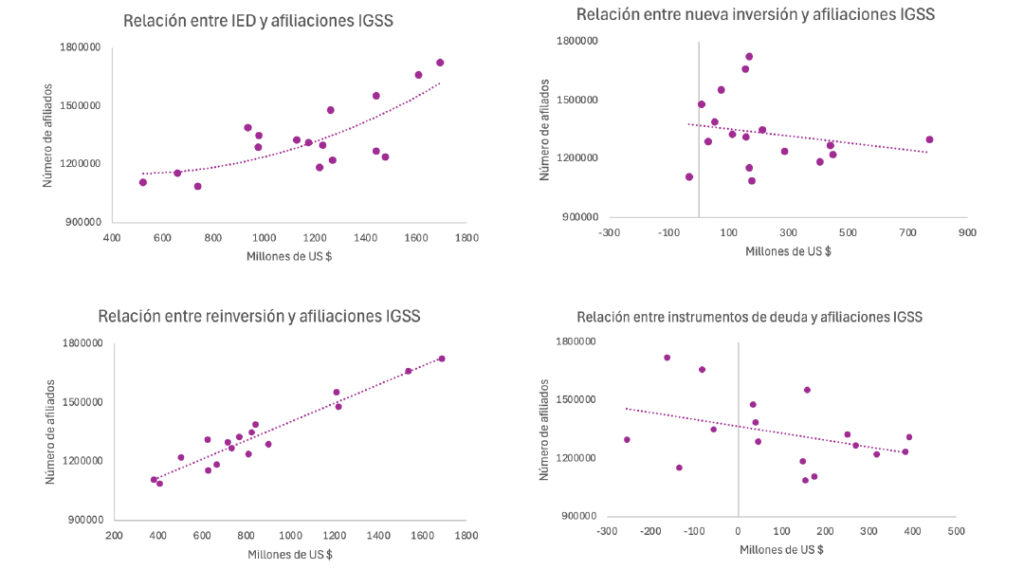

This analysis seeks to identify possible correlations between total FDI and the number of registered employees, as well as between each of its components—equity and new participations (new investment), reinvestment of earnings, and debt instruments—and the number of affiliates. The goal is to determine whether a statistically significant relationship exists between these variables.

Figure 7. Correlation Analysis between FDI Components and IGSS Affiliations

The results, while not aiming to establish direct causality from any FDI component, are as follows:

• Total FDI and Affiliations: The correlation coefficient (r) was 0.72, reflecting a strong positive relationship between both variables.

• New Investment and Affiliations: With r = -0.20, the result suggests that new investment does not exhibit a significant relationship with formal job creation. This may be due to the relatively small share that new investment has historically represented within Guatemala’s total FDI.

• Reinvestment and Affiliations: With r = 0.96, a very strong relationship is evident, which also helps explain the high overall correlation between total FDI and formal employment.

• Debt Instruments and Affiliations: With r = -0.38, the result indicates a weak inverse relationship. However, this component requires more rigorous analysis to confirm its statistical significance.

In summary, FDI in Guatemala historically driven by over 70% reinvestment of earnings maintains a significant association with the generation of formal employment. In contrast, new investment shows no strong relationship with job creation, likely due to its comparatively low inflows over the years.

Final Observations

After conducting both the conceptual review and the quantitative analysis of FDI figures over the years and across the countries in the region, several key conclusions can be drawn:

• Regional Structure of FDI: Throughout the region, total FDI has been predominantly composed of reinvestment flows. However, there are exceptions—such as Colombia and Costa Rica—where this pattern does not always hold. Despite these differences, there is a clear regional trend toward a declining share of new investment and an increasing importance of reinvestment.

• In Guatemala, reinvestment has historically represented around 75% of total FDI, reflecting the confidence of companies already established in the country. Furthermore, the correlation between FDI and formal employment is particularly strong, showing that these capital flows play a fundamental role in job creation and labor formalization.

• Guatemala and Honduras have very similar FDI structures in terms of composition. However, when analyzing the volumes, Guatemala occupies an intermediate position within the regional context.

• FDI inflows to Guatemala have shown a significant increase over the last four years. Likewise, the analysis of historical cycles reveals that FDI in the country tends to follow approximately eight-year patterns, suggesting that the average growth observed since 2021 could continue at least until 2028.

References

Ministry of Economy (2016). What is Foreign Direct Investment? Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.gob.mx/se/articulos/que-es-la-inversion-extranjera-directa

Bank of Guatemala (2021). Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Guatemala. Guatemala.

International Monetary Fund (2009). Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition (BPM6).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2008). OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment (Vol. IV).

Central American Monetary Council (n.d.). SECMCA. Retrieved from https://www.secmca.org/

Central Reserve Bank of El Salvador (n.d.). Central Reserve Bank of El Salvador. Retrieved from https://www.bcr.gob.sv/

Central Bank of Honduras (n.d.). Central Bank of Honduras. Retrieved from https://www.bch.hn/

Central Bank of Nicaragua (n.d.). Central Bank of Nicaragua. Retrieved from https://www.bcn.gob.ni/

Central Bank of Costa Rica (n.d.). Central Bank of Costa Rica. Retrieved from https://www.bccr.fi.cr/SitePages/Inicio.aspx

Central Bank of the Dominican Republic (n.d.). Central Bank of the Dominican Republic. Retrieved from https://www.bancentral.gov.do/

Bank of the Republic, Colombia (n.d.). Bank of the Republic. Retrieved from https://www.banrep.gov.co/en

Central Reserve Bank of Peru (n.d.). Central Reserve Bank of Peru. Retrieved from https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/

Bank of Mexico (n.d.). Banxico. Retrieved from https://www.banxico.org.mx/

Guatemalan Social Security Institute (IGSS) (n.d.). IGSS. Retrieved from https://www.igssgt.org/

Annexes

Descriptive Analysis of FDI in Its Quarterly Series for the Selected Region

Table 1. Descriptive Analysis of Quarterly FDI in the Region

Descriptive Analysis of FDI/GDP by Country

Table 2. Descriptive Analysis of FDI Participation over GDP

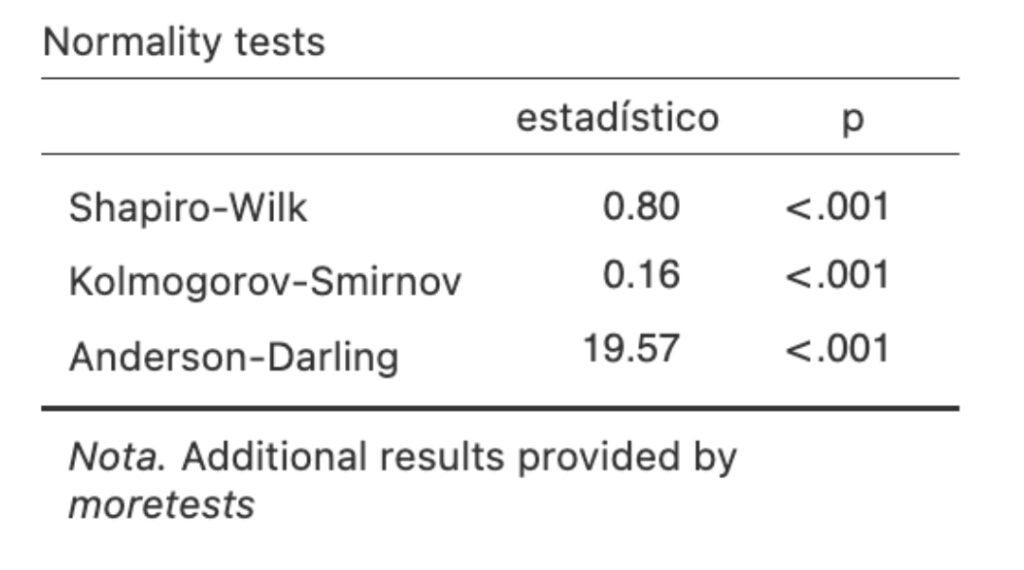

Normality Test for FDI/GDP

Illustration 1. Normality of %FDI/GDP

As expected, the test results show significant differences in the median weight of FDI over GDP among the analyzed countries.

In Guatemala, the difference is significant compared with all other countries, since in those economies FDI has a greater relative weight. For example, in 2024, FDI in Guatemala represented only 1.5% of GDP. The only exception is Mexico, where the difference is explained by the much larger size of its economy.

In Honduras, no statistically significant difference is observed in FDI/GDP compared with Costa Rica, Colombia, and Peru. Both Guatemala and Mexico show a smaller FDI/GDP proportion than Honduras.

In Costa Rica, the FDI/GDP ratio is similar to that of Honduras and Peru, and significantly higher than that of Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico.

In Colombia and Peru, the difference is not significant, with Colombia being the third country with the lowest FDI/GDP ratio among those analyzed.

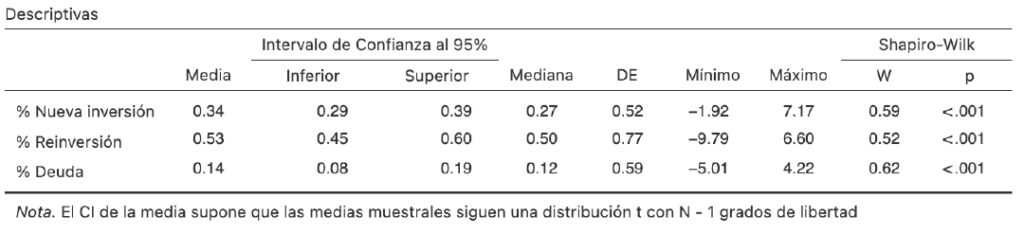

Normality Tests for FDI Components in the Region

Table 3. Descriptive Analysis of Quarterly FDI Components in the Region, 2008–2025

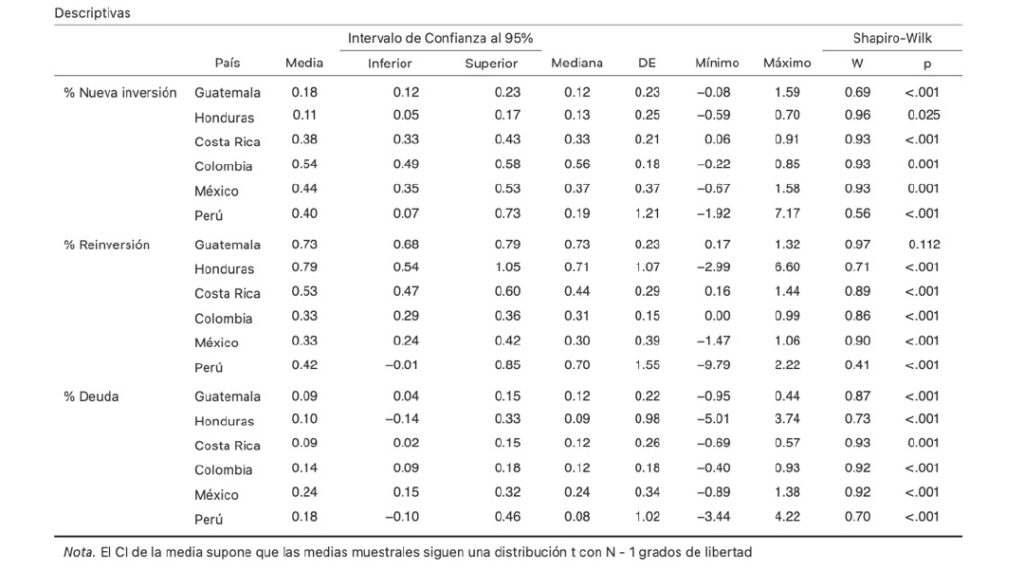

In Table 4, it is evident that only reinvestment in Guatemala follows a normal distribution; in contrast, for the rest of the countries and components, the distribution is not normal, which directs the analysis toward nonparametric statistical methods.

From a descriptive perspective, the following key findings stand out:

• Guatemala is the second country with the lowest average participation in new investment (18%), just above Honduras, and at the same time the second country with the highest average participation in reinvestment (73%).

• Colombia leads in average participation of new investment, exceeding 50%.

• The FDI composition in Mexico is quite balanced among its components, standing out as the country where debt instruments have the highest share in the region (24%). Peru also stands out for the composition of its FDI and the participation of debt instruments, though to a lesser extent than Mexico.

Table 4. Descriptive Analysis of Quarterly FDI Components by Country, 2008–2025

Normality Tests for FDI Components by Country

Illustration 3. Normality Test for % New Investments

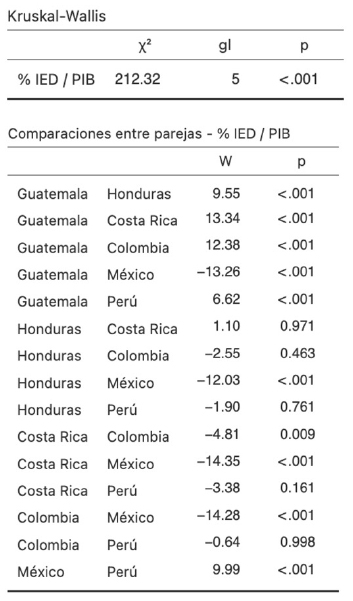

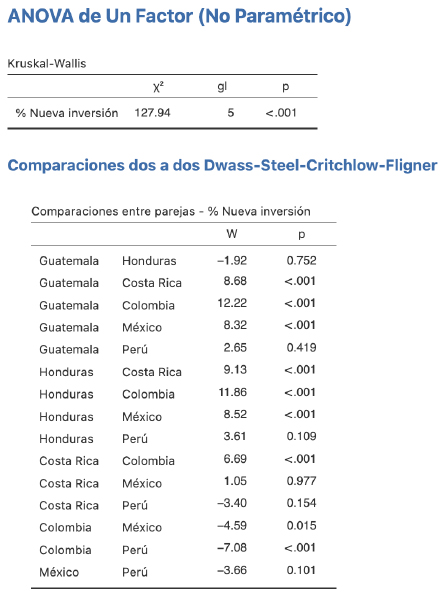

The results indicate that the three components of FDI do not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, median difference tests were applied using the Kruskal–Wallis test and its corresponding Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner pairwise comparison method.

Illustration 4. Differences in % of New Investment

The Kruskal–Wallis test results show statistical evidence that at least one of the analyzed countries behaves differently regarding the importance of new investment within total FDI.

The pairwise comparisons reveal that, for Guatemala, the share of new investments is significantly lower compared with most countries in the region—except Honduras, whose structure is very similar.

In Peru, multiple fluctuations make precise measurement difficult. In Costa Rica, differences with Mexico are not statistically significant, while in Colombia, the share of new investments is significantly higher compared with the rest of the countries analyzed.

Illustration 5. Differences in % Reinvestment

Similarly, the Kruskal–Wallis test indicates that there are statistically significant differences among the medians of the reinvestment participation series.

In this sense, the percentage of reinvestment between Guatemala and Honduras is practically the same, with a p-value close to 1.

The difference between Guatemala and Peru is not significant, and reinvestment proves to be more important for Guatemala than for the rest of the countries in the region.

Honduras shows a pattern similar to that of Guatemala.

For Costa Rica, the participation of reinvestment is practically as relevant as in Mexico. In contrast, in Colombia, reinvestment is significantly less important compared with the region as a whole.

Illustration 6. Differences in % Debt Instruments

For the third FDI component, it is also expected that significant differences exist among the countries.

In this regard, for Guatemala, the share of debt instruments within FDI is lower, with the significant difference found only when compared with Mexico.

In the case of Honduras, the differences relative to the rest of the region are not statistically significant. Costa Rica, like Guatemala, shows significant differences only with Mexico.